There’s a lot of reading to do when you’re pregnant, from “What To Expect When You’re Expecting” to supply checklists and gift registries. So, it’s understandable if you skimmed over some of the biological topics, like how the umbilical cord is developed. But it’s literally your baby’s lifeline. Knowledge about it can help you understand the role of the umbilical cord and why it’s rich with such valuable contents.

The Ultimate Connection

You can’t underestimate the umbilical cord and how it connects you to your baby. Some have likened it to the cord that tethers an astronaut to their mothership in space. You can sing to your baby and rub your belly, and it’s nurturing—but it’s this tangible link that’s biologically nourishing.

That’s why a baby’s first moments in our world can be such a shock for them. First, the rush of shivery air. Then the cutting of the cord, the baby’s own food delivery service. You’ll have the belly button left behind as a reminder of when you two were physically attached. And if you choose to save the cord blood and tissue, you’ll also have a rare souvenir that just might save a life one day.

Your baby is well on its way before the umbilical cord makes an appearance. They will already be the size of an orange seed before the cord begins to form. The embryo will be starting to resemble an actual fetus, with a pre-spinal cord and brain.

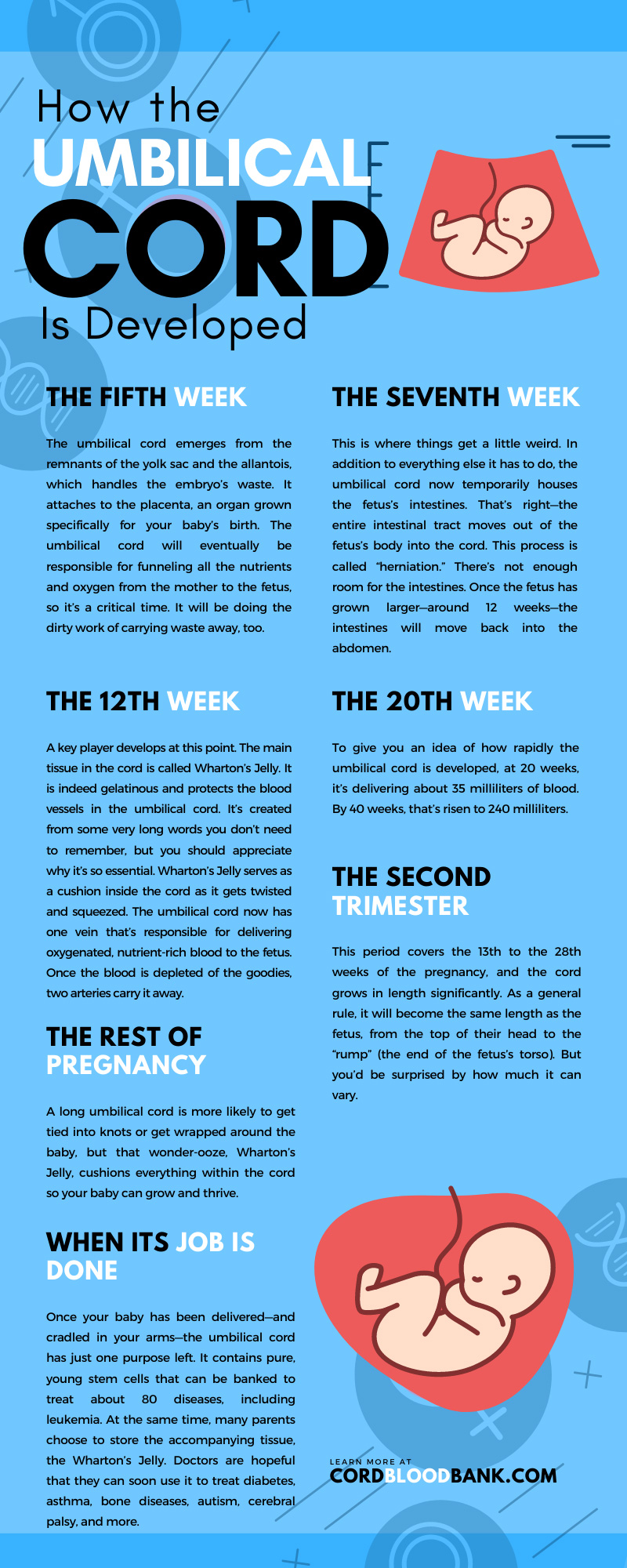

The Fifth Week

The umbilical cord emerges from the remnants of the yolk sac and the allantois, which handles the embryo’s waste. It attaches to the placenta, an organ grown specifically for your baby’s birth. The umbilical cord will eventually be responsible for funneling all the nutrients and oxygen from the mother to the fetus, so it’s a critical time. It will be doing the dirty work of carrying waste away, too.

The Seventh Week

This is where things get a little weird. In addition to everything else it has to do, the umbilical cord now temporarily houses the fetus’s intestines. That’s right—the entire intestinal tract moves out of the fetus’s body into the cord. This process is called “herniation.” There’s not enough room for the intestines. Once the fetus has grown larger—around 12 weeks—the intestines will move back into the abdomen.

The 12th Week

A key player develops at this point. The main tissue in the cord is called Wharton’s Jelly. It is indeed gelatinous and protects the blood vessels in the umbilical cord. It’s created from some very long words you don’t need to remember, but you should appreciate why it’s so essential. Wharton’s Jelly serves as a cushion inside the cord as it gets twisted and squeezed.

The umbilical cord now has one vein that’s responsible for delivering oxygenated, nutrient-rich blood to the fetus. Once the blood is depleted of the goodies, two arteries carry it away.

The 20th Week

To give you an idea of how rapidly the umbilical cord is developed, at 20 weeks, it’s delivering about 35 milliliters of blood. By 40 weeks, that’s risen to 240 milliliters.

The Second Trimester

This period covers the 13th to the 28th weeks of the pregnancy, and the cord grows in length significantly. As a general rule, it will become the same length as the fetus, from the top of their head to the “rump” (the end of the fetus’s torso). But you’d be surprised by how much it can vary.

The more a baby wriggles about in the womb, the longer the cord. Eventually, the typical umbilical cord will grow to between 20 and 24 inches, and one to two centimeters in diameter. But a shorter cord can be just 13 inches or less and still do the job successfully. Longer cords can extend to 32 inches or the length of two bowling pins laid end to end.

The Rest of Pregnancy

A long umbilical cord is more likely to get tied into knots or get wrapped around the baby, but that wonder-ooze, Wharton’s Jelly, cushions everything within the cord so your baby can grow and thrive. Some mothers like to think of the umbilical cord as their baby’s first toy, as they reach and hold onto it as they float in the comfort of the womb. That’s why so many volunteers crochet toy octopuses for premature babies; their tentacles are comforting to grab onto so the babies won’t pull out their tubes and monitors.

When Its Job Is Done

Once your baby has been delivered—and cradled in your arms—the umbilical cord has just one purpose left. It contains pure, young stem cells that can be banked to treat about 80 diseases, including leukemia. At the same time, many parents choose to store the accompanying tissue, the Wharton’s Jelly. What is cord tissue used for? Presently, research is ongoing, but doctors are hopeful that they can soon use it to treat diabetes, asthma, bone diseases, autism, cerebral palsy, and more.

Fun Umbilical Cord Facts

It Has No Nerves

When the cord is clamped and cut, the baby and the mother feel no pain. It does, however, feel strange to whoever is cutting it. Some have described it as similar to “cutting into calamari.”

It’s Self-Sealing

If no one was there to cut the cord, it could achieve closure on its own. Once the baby no longer needs it, the Wharton’s Jelly starts to harden and shrink. The blood vessels are closed off, naturally clamping together.

It Was Preserved in Many Cultures

In Turkey, parents buried the umbilical cord in a place of knowledge that could influence their child’s future occupation. Many Native American tribes kept the dried cord in a pouch the baby could wear around their neck. In Japan, the cord was kept in a dedicated, decorated wooden box.

A child only comes into contact with an umbilical cord at the very start of their life. But the stem cells and tissue a cord holds could be a valuable healing source for years. At New England Cord Blood Bank, we protect these near-miraculous materials in optimal conditions until your child needs them. Visit our site to find out more.